The Failings of a Human Being

Trigger warnings: mental health issues, discussions of suicidal ideation, illness, death

I’m not a perfect person. I’ve never claimed to be. I’ve made mistakes in my life, some small, some big, some maybe even unforgivable. Some might say it’s part of being human, but I tend to hyper-focus on things, and have trouble letting go.

I don’t need advice. I don’t need sympathy. Whatever you’re feeling about what you read next, chances are you might want to offer some kind of platitude. Don’t. That’s not what this is for. I’ll remind you of that again later on.

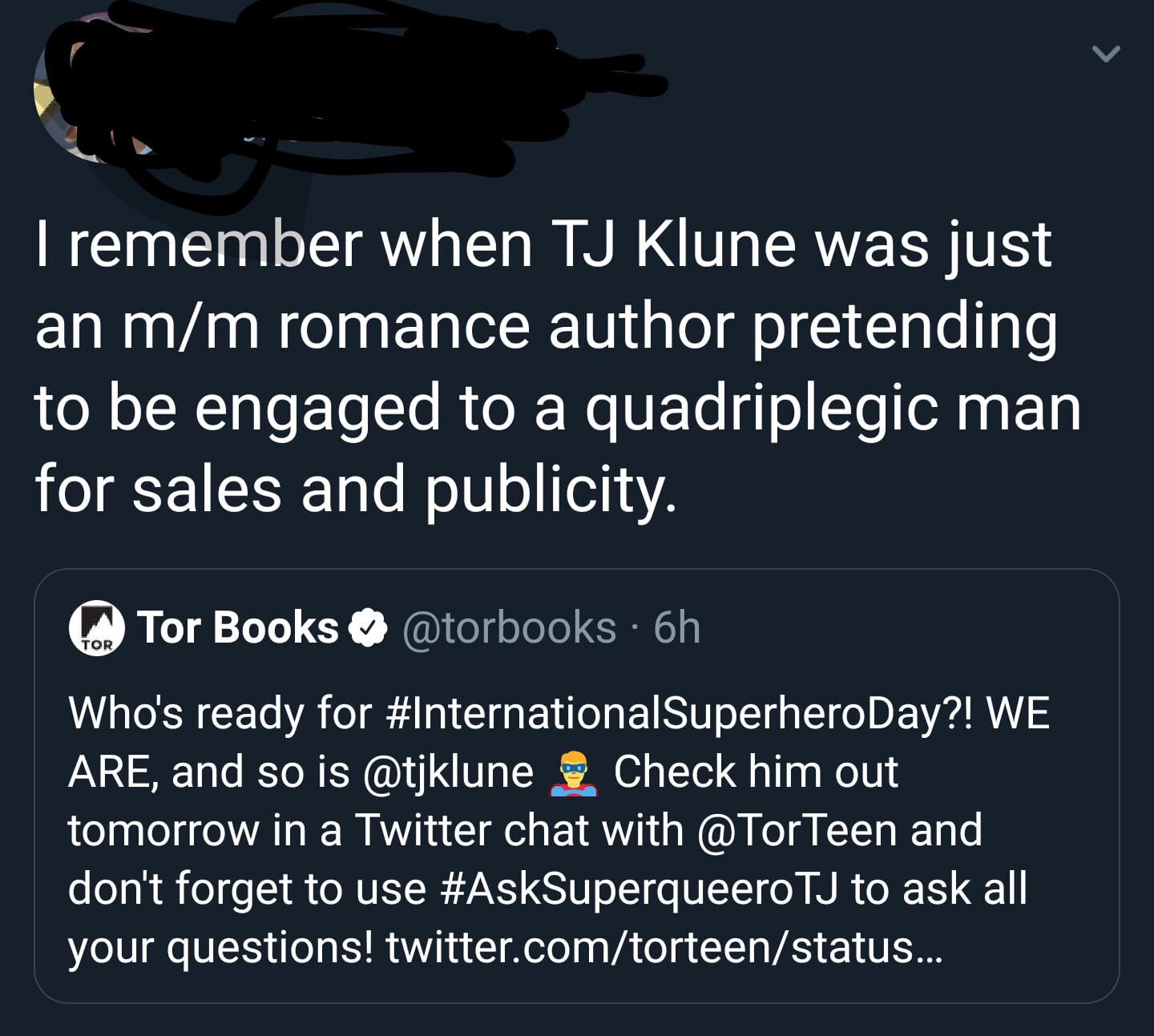

Someone sent me a screenshot of a tweet. I’ve posted that screenshot below. I’ve hidden the person behind the account. Please do not look it up. Do not comment on it. I don’t want nor need your defense.

The tweet:

First, I don’t know who this person is. Frankly, that’s not even the issue. The tweet itself is. That is a pretty goddam serious accusation, and one I don’t take lightly. My first reaction upon seeing the screenshot was an intense fury like I haven’t felt in years. I’m not an angry person. I try to be as level and calm as someone like me can be. But seeing that? Holy shit, I was rabid with anger. So much so that if this person was in front of me, saying it to my face, I probably would have lashed out physically, not stopping until someone pulled me off or enough blood had been spilled to bring me to my senses.

Anger gave way to sadness, a bone-deep ache that I carry with me all the time. Why, I asked myself, would someone who doesn’t know me, didn’t know Eric, say something like that? What is so wrong with a person that they think something like that is okay?

First and foremost, a denial: the claim that I used Eric Arvin for sales and publicity is a disgusting fabrication. The fact that this person felt like they could say something like that is on them, not me. I have my own moralistic failings as human being—which I’ll get to in a moment—but this person is gross. Would they say the same to my face? I highly, highly doubt it.

However.

I failed as a human being.

I met Eric online way back in 2011, after my first book came out. I don’t remember how we connected, but we did, through FB messenger and email. He was delightful to talk to, funny and charming and witty in ways I can’t even begin to describe. I was smitten with him, even though I hadn’t met him. And why not? In addition to being hysterical and lovely, he was beautiful, a big beefy guy who was also shy, but…I don’t know. There was this light to him I can’t explain. I’ve never seen it in anyone before or since.

And his books! My god, his books. If only I could write how he did, I’d never want for anything again. His prose was sublime, gorgeous, haunting. Read Woke Up in a Strange Place, if you need proof. It’s one of the best queer books I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading. One of the best books, period.

Eric was disabled. One side of his body didn’t function as well as the other. He walked with a cane because of his left leg, and his left hand wasn’t completely functional. I don’t need to explain why, just that he’d had health issues for a long while, but he still made the most of it. There were days he was frustrated by it, but there were even more days when he made the most of it, and that counts.

I didn’t know patience before I met him, at least not really. Eric had to move slow wherever he went. I didn’t. My body, like my brain, felt like it moved at a billion miles per hour. When I finally met him in 2012, I was instantly head over heels (though you can sure as shit bet I tried—and failed!—to play it aloof). Two nights later on this trip, he kissed me, or I kissed him, I don’t know. Someone leaned in, and that’s all she wrote.

He lived in Indiana. I lived in Arizona. Problem, yes, but not for us. We made the most of it. It was easier for me to travel, so I did, going to Indiana quite a few times. In 2013, he came and lived with me for the summer in Tucson. It was an adjustment for both of us—me being used to my independence, him never having one so far to live away from home for too long of a time. But we made it work. So much so, that as the summer drew to an end, we decided we wanted to make it permanent. Not in Arizona, though. He hated the heat.

I worked for GEICO at the time. I went into work the day after he left to go back home, and started looking for job postings with the same company in the US. Two positions opened up: one in Seattle, one in Fredericksburg. I liked small towns, and I’d never been to the East Coast. So I talked it over with him. He agreed Fredericksburg sounded good. So I applied.

And got the job.

The next weeks were a whirlwind. Not only was I moving across the country to a place I’d never been before where no one I knew lived, I was doing it with a person I really loved. I’d never lived with a partner before. So, what did I do to try and alleviate some of the fears I had?

On the one year anniversary of us getting together, I asked him to marry me. He said yes. And then we went to Fredericksburg to begin the rest of our lives.

We got six weeks.

Eric began to have some motor-skill issues. His legs felt weird. I didn’t think much of it as I went to work, telling him to keep me informed. I got a text right as I’d gotten to work. He’d collapsed in the bathroom at our house. He wasn’t hurt, not exactly, but he couldn’t stand. His legs didn’t work.

Worried, I went home.

The next weeks and months are—even now—a haze. I remember bits and pieces. I called the ambulance as soon as I got home. They took Eric to a hospital here in Fredericksburg, but, after doing a scan, decided to move him to Richmond, an hour away, to a bigger hospital. They wouldn’t tell me why. At least, I don’t remember them telling me why. I got choked up. Eric, ever the calm person that he was, told me it would be fine, that he’d see me in Richmond when I got there.

He was intubated by the time I arrived in Richmond, and pumped so full of drugs, he could barely blink. He’d started having trouble breathing on the way down in the ambulance. They’d done what was necessary in order to keep him alive. I had never been so scared in my life. I’m a writer, but even now, words fail me to adequately explain how terrified I was right then. I broke down. I couldn’t stop crying.

Friends came. His family came.

Later, we would find out the truth. A cavernous hemangioma. A tumor. A benign tumor. But the problem was the placement. This benign tumor was growing on Eric’s brain stem. The brain stem connects the brain to the rest of the body, sending electrical impulses to allow us to do…well, most everything. Like walk. This tumor was putting pressure on the brain stem.

In addition, there’s something called the phrenic nerve in the same area of the body. The phrenic nerve provides exclusive control to the diaphragm. In other words, you need it to breath on your own. Every inhale you take is because of the phrenic nerve. The tumor was pressing against that, too, which is why Eric had problems breathing.

He had two courses of action: do nothing, and agree to a death sentence. Or go into surgery on one of the worst places to have surgery. No one sugar-coated this for us, least of all the surgeon. I learned very early on that surgeons don’t have empathy. The nurses—the wonderful, tremendous nurses—do. That’s just how it was, at least in our experience.

He decided to have the surgery. It lasted for hours and hours. The tumor was removed. But Eric was paralyzed from the neck down. He would be ventilator dependent for the rest of his life.

Everything I knew crumbled around me.

And oh, did I sink into the darkness of it all.

I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know how to act. I didn’t know how to be. I got it in my head that I needed to buy a house in Fredericksburg. That I could—even though we didn’t have any real friends or family in the area—take care of him myself, on top of working 50 hours a week and trying to have a writing career. I could do this. He was my fiance, and I could do it.

He was in the hospital for months, from the beginning of December 2013 to March 2014. During that time, friends put together a fundraiser, raising a lot of money for Eric’s care, for friends and family to have lodgings while in a state and city they didn’t live in. Others ran that money in the first months. I never took a cent for myself to keep. Anything I used was for Eric. At the end, I turned over all the funds to his mother, because it wasn’t for me.

Eric returned home to Indiana after a disastrous stay in another hospital, the less said about that, the better.

So there I was, alone a rental house in Fredericksburg, with nothing but myself.

And I got so angry.

I got angry at my friends for going back to their lives like everything I had hadn’t just been destroyed.

I got angry at my family not doing more even though they’d done enough. Eric’s family too, who were grieving just as hard as I was, but in this mindset, I couldn’t see that.

I got angry at our friends who gave up their time and money and so much more.

I got angry at everyone on social media, posting happy things and going about their lives like the world hadn’t just come to an end.

I got angry at Eric. How dare he let this happen, even though he had no control over it? He still smiled alot. Brave, strong, wonderful Eric still put on a brave face, even though his head was the only thing he could move, and how dare he.

I let myself drown in my own toxicity. I was poison to everyone and everything. I thought I could hide it. I began house hunting. I found a house. I bought a house (with my own money, of course). Eric’s mother asked me repeatedly if I was sure, that Eric could stay in Indiana, because he had her, and so many extended family members willing to chip in and help out. In Fredericksburg, there was only me. But I was trying to stay afloat on this sea of toxicity, so I plowed ahead, manic and half out of my mind.

It was when I first moved into this house that it started to sink in. I remember the day it hit: I was trying to hang a picture. I couldn’t get it straight. Finally, I lashed out, knocking it off the wall. It shattered, but I didn’t hear it. I had collapsed on the floor in one of the most severe, debilitating panic attacks I’d ever had.

Suicide seemed like the best option. On three separate occasions, I almost went through with it, the last of which involved me climbing into the bathtub full of cold water to numb my skin so I wouldn’t feel the pain in my wrists. But I didn’t. Why? Not because I figured it was the wrong thing to do. No. I was too scared. A coward.

This isn’t meant for sympathy. I don’t need it. Save your words for someone who could use them. I’m merely stating fact. That’s how it was for me. I drank too much. I became reckless, lashing out at anyone and everyone. I took a social media break for months because honestly? I was sick and tired of seeing happy people going on with their lives. I hated all of you.

I failed Eric. Physically, moralistically. I…disappeared, curled in on myself and didn’t speak to anyone about anything. I got up in the mornings with maybe an hour of sleep. I went to work. I came home. I stared at the walls until it was time to get up again and go to work. I didn’t go to therapy. I didn’t take my medication. I didn’t eat. I didn’t sleep. I told Eric he was better off in Indiana, that I couldn’t help him, not as I was. Do you know how that felt? I hope not. It was the worst feeling I’ve ever had. Nothing before or since has ever compared.

I was basically dead, even though my heart still beat.

And I’ve stayed that way for years. Oh, I finally went back to therapy (was essentially forced to by some awesome people). I got back on my meds. The suicidal ideation was—and is—still there, but it’s something I know how to control. And if there are days when I can’t control it, I know how to reach out for help.

But this guilt is mine, and mine alone. I’ve carried it with me ever since. I’ll carry it with me forever. I don’t deserve to let it go, and I won’t. When good things happen to me, I get happy about them, but it doesn’t get too far because I temper it, knowing what I’d done. I could tell you the money I donate to causes for people like Eric every year, but that just sounds like I want your sympathy. I don’t. I could tell you that I try and do one good thing every day because of Eric, but that again sounds like I’m trying to absolve myself. I’m not. I was weak. I wasn’t as strong as a good person should have been, and I know that. My life now is quiet. It’s easier that way. I have my ghosts I deal with every day, and I won’t inflict those ghosts on anyone else. I’ve made the decision to be alone from now on, because that’s how I can function. It’s my penance, and one I’ve accepted. Again, I don’t need advice or sympathy or anything like that, so please don’t. This is my normal.

Eric died in December of 2016 in Indiana. People on ventilators often succumb to the same thing: pneumonia. The body isn’t meant to live for a long time with a breathing tube sticking out of a throat.

I died back in 2013. I drowned in my own weakness, my own toxicity. Yet, I’m still alive. I’m not as bad as I was years ago, but there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about Eric, and my failures as a human being. That will be with me, always. It’s my burden to carry. I’m used to its weight now. I can carry it, because I have to.

So no, random tweeter: I wasn’t “pretending” to be engaged for publicity and sales. But trust me when I say that nothing—nothing—you can spit about me won’t make me feel any worse than I already do. I know my failures. I’ve owned them. They are my ghosts, and I haunt them just as much as they haunt me.

The only person that matters in all of this is Eric. And one day, I’ll stand before him again and tell him all of this. If he forgives me, good. If he doesn’t, that’s his choice, and I won’t blame him.

I know my failures as a human being, random tweeter. But the question is: do you know yours?